MAMI Day 4

Halfway through Olivier Assayas’s latest film Doubles Vies, which is also that rare film to have fully earned the ‘drama/comedy’ classification, a woman turns to the ‘auto-fiction’ novelist she’s having an affair with and demands to know why he has changed certain details of their affair in his latest novel Full Stop—never has an on-screen novel been more perfectly titled—and not other details. “For storytelling,” the novelist says, feebly. “I thought you hated storytelling,” the woman retorts. “Oh, I’m walking that back,” he replies, with no trace of irony.

I’m not sure if I’ve said too much already, or too little. Spoilers are inevitable, but how to narrate (the experience of watching) Doubles Vies is a challenge that is indicative of the particular preoccupations of the film. Storytelling is a quotidian concern in Assayas’s superbly straight-faced examination of the lives of two middle-class Parisian couples and all their friends and colleagues whose lives collide haphazardly with theirs. The couples, who variously work as a famous TV actress (Selena, portrayed with such ease by Juliette Binoche), a critically-acclaimed publisher (Guillaume Canet, whom I adored watching every second as Alain, Selena’s husband), a novelist verging on a failed career (Léonard, played by Vincent Macaigne), and a high-profile lawyer (Nora Hamzawi, as Léonard’s charismatic wife, Valérie), are more wary of what may be believed to be the truth of their lives than of the shibboleth of veracity itself.

We spend a fair amount of screen-time switching between households, dinner parties on friends’ sofas, cramped restaurants, and bedrooms, watching impeccably-scripted dialogue volley between people who, above all else, are skilled in the art of bourgeois conversation. They’re pathetic, but funny. The men wear tailored clothes. The women work most of the time, and they look good all of the time. The characters read Lampedusa—not carefully, though—they watch Haneke, they question authors at book launches and their post-coital routines include disagreeing over the impending extinction of print. They talk about the increasing digitisation of the world, they agonise over the rift between writers and readers, and they heatedly debate whether socialist politicians can be both in search of a career and also serve people honestly. It’s hard to take your eyes off the characters, obnoxious as they—we—are, because they are so sure of themselves, even as the camera playfully pans over whole rooms, reminding us of the unstable architecture of any argument, of how it unfolds—how you take or leave space during a conversation, where he moves when he’s restless, the corner of the kitchen where you’re likely to stop engaging, how she slouches when she’s about to concede a point, the motion you make towards unplugging your phone and tablet because a dwindling response is in sight, how he leans lightly against the window when he’s waiting for your comeback.

You’re as invested in these conversations as the characters are, because you’ve had probably had these arguments yourself, or you thrive on conversations like these—or, as the film wears on, you realise, perhaps you thrive on the rush of intimacy that enables these conversations in the first place and fogs them afterwards. Alain argues lightly with his wife about publishing Full Stop because he feels the women are objectified in a work of non-fiction but seconds later, a shadow crosses his face as he listens to her say, maybe the women like it, and in his slightest slump over the table, we are simultaneously embarrassed for and tender towards him. A hilarious break-up moment turns devastating when Selena interrupts the man she’s breaking up with by casually turning to the bartender to say that she wants another orange juice without the ice, please. Léonard argues passionately for a dematerialised literature culture, embodied by socialists like him who disdain the commodification and want the art back, and his publisher Alain, who has been listening as he packs up, stands at the door and says, “Your radicality is also narcissism. It’s the most valuable commodity.” He smiles. How you remember an argument is marked by how you feel, not by events. Assayas knows this.

While Assayas’s interest in the mundane ways in which technology affects us is long-standing, calling Doubles Vies a film about the perils of digitisation makes about as much sense as calling Personal Shopper a supernatural film, or Kiarostami’s Certified Copy—which, to me, is the older, bolder sister of Doubles Vies—a film about art criticism. In each of these films, la numérique, or haunting, or art is used as a springboard to ask more probing questions about storytelling, loss and authenticity respectively. Assayas’s talent for filming people in their element is terrifying only because when they are at their most engrossed, they are also at their most vulnerable—and therefore, at their most magnetic. What constitutes shakier earth than the potential of interrupted intimacy of any sort?

I realised only as the credits rolled that the french title of the film is Doubles Vies, or what I would have read as “double lives.” I wanted to re-watch the film immediately. All this time, I had been calling the film by its only too appropriate English title, Non-Fiction.

*

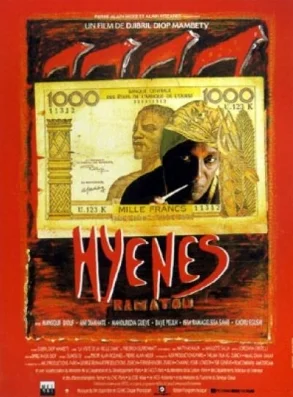

The 1992 poster for Hyenas. Source.

Fifteen minutes after exiting the Assayas, I seated myself in a packed cinema hall to watch Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes, a 1992 Senegalese adaptation of The Visit, a play by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, a German-Swiss dramatist. I went into the film without reading anything about it, as I’ve tried to do for most films during this festival, and so I was completely unprepared for the impressive but slow, horrifying transition that the film makes from light satire to dystopia. In an impoverished village named Colobane in postcolonial Senegal, news spreads that Linguere Ramatou (essayed by the stunning Ami Diakhate), a previous inhabitant of the village, has returned “richer than the World Bank” from across the Atlantic. Amongst the people eagerly awaiting the return of her—and her wealth, crucially—is a grocer named Dramaan Drameh, her former lover. Gradually, it is revealed that Ramatou is happy to use her money to improve the living conditions of the people of Colobane, but only if they are willing to execute Drameh, who she says abandoned her after impregnating her several years ago. Ramatou was then sent away from the village. A year later, she lost her daughter, and then many years later in an accident, most of her body. She has returned, having earned her millions through sex work, with a body of metal and an ironclad will to see Drameh lose his life, if the people of Colobane are willing to bloody their hands and consciences for material gains.

Hyenas is a sharp, dazzling critique of neocolonial Africa and the ‘development’ institutions associated with the continent, such as the IMF, and even is, as the critic Kenneth Tynan says of the play, “a satire on bourgeois democracy.” But what gripped me was the portrayal of Linguere Ramatou, a woman who possesses the ability to see through the hypocrisy of men and exploit the impulses of capitalist patriarchy (what we could also call a ‘mob’, in this case) because she understands the perversity of man so clearly. Ramatou spends most of the film watching the people of Colobane from her distant posts, all of which are lonely, God-like perches: by a sapphire sea, from the top of a hill, on sand dunes. She asks for the life of a man as compensation for the years that were taken from her, but in truth the situation that she creates goes far beyond the question of vigilante justice: she promises the hyenas of Colobane a life free of debt that they incur precisely because they desire the hollow promises of neoliberalism, as she knows they do. In other words, her revenge isn’t in facilitating an act of murder—that is a symptom—but in summoning the implosion of the place that once rejected her. Drameh may not survive, but he spends most of the second half of the film warning his friends not to destroy themselves.

Reading the film as a vicious critique of civic justice hastened under the demands of a neoliberal enterprise embodied by a woman who was once herself on the fringes (ah, the vengeful sex worker—not!) is only valid if we view Ramatou as a woman who has understood and been betrayed by the evils of capitalism so thoroughly that the scope of her revenge-plot exceeds far beyond the sacrifice of one man in order to control the ecosystem of the land. Hyenas appear through the film (from Uganda), as do monkeys, elephants (from Kenya) and vultures, in metonymic flashes.

Ramatou’s character is a powerrful articulation of the terror that neoliberal feminism enacts as/through patriarchy; her solidarity is not with the oppressed, and her interest is in turning oppressor. There is no triumph at the end for anyone except Ramatou, who knows this from the start. Before Drameh leaves, she tells him they can be together after he dies. It’s a bizarrely touching moment, because they are the only two people who understand the destruction that awaits Colobane.

Mambéty’s radicality also emerges through his film-making. While he rejected the idea of a “style” of film-making himself, he noted that “cinema is magic in the service of dreams.” The cinematic texture of the film evolves from a proto-realist, documentary style to one that is almost incantatory and surreal by the end. Colours are amplified, palettes distilled. A shot of Drameh driving a red car in circles around the desert on his way to face his sentence is extraordinarily chilling. Elephants morph into steamrollers. It’s the beginning of the end. If you weren’t breaking into a sweat before, you almost certainly are now.

*

I awoke this morning, feeling anxious at the prospect of no films today. You don’t go cold turkey on a film festival. I go back tomorrow to the calcified comfort of a darkened cinema hall but I want to say, as I look round my room now, that a little light isn’t all bad.